Water is an essential component to the development of communities. Not only for the individual consumption and hygienic needs of the residents, but for the hydraulic power it can provide that facilitates a variety of tasks. At one time, farmers ideally found a water source uphill so that water reached the farm by the sheer force of gravity. This allowed them to avoid digging a well or pumping water. Waterways that have a flow strong enough to work a mill were highly sought-after and quickly exploited when found.

Mills: A Source of Development

At the end of the 1790s, even before the official concession of the Township of Sutton, grain mills and sawmills straddled Sutton River at Shepard’s Mills (today known as Abercorn), and on the property of William Huntingdon at the heart of Sutton village, near the junction of what are now Principale Sud and Mountain Roads. In 1814, Stephen Westover built grain and saw mills on a stream at the foot of Mount Echo. Mills were also built on Brookfall, Eastman, and Dufur streams in Glen Sutton.

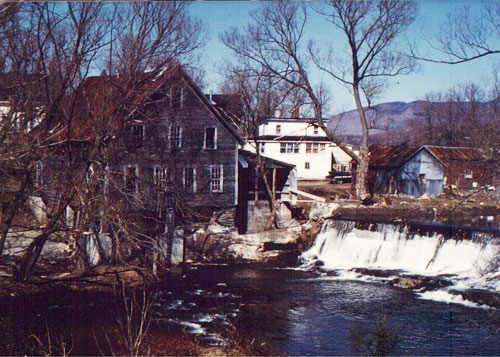

There are no remains of these first mills, although some have since been replaced (as is the case in Abercorn). New mills that later came into the picture include the one built on Sutton River by Omie Lagrange in 1846 near what is now known as Highland Road. Omie Lagrange, who already ran mills in Frelighsburg, came from a family of millers. It is easy to see how the waterfall at this point in the river caught his expert eye.

A grain mill, the Lagrange Mill was taken over by Reuben Mills in the early 1860s. Mills, as his family name would suggest, also came from a family of millers. His father Moses contributed to the installation of several mills, including the Westover Mill and the one built by Paul Holland in Knowlton. Old maps show a Mills Road that no longer exists today, but ran from a little bit before Maple Road up towards Highland Road (see map). It was common practice at the time to name roads after the main owner of the waterfront property.

Reuben passed on the torch to his son, Frederick, when he was no longer able to run the mill due to age. Interestingly, despite his inability to work due to age, Reuben died in 1903, five years after his son who passed in 1898. It is not currently known whether anyone from the Mills family took over the mill after their deaths until it stopped working in 1911.

Reuben Mills is buried at Fairmount Cemetery, just across the road from where the mill once stood.

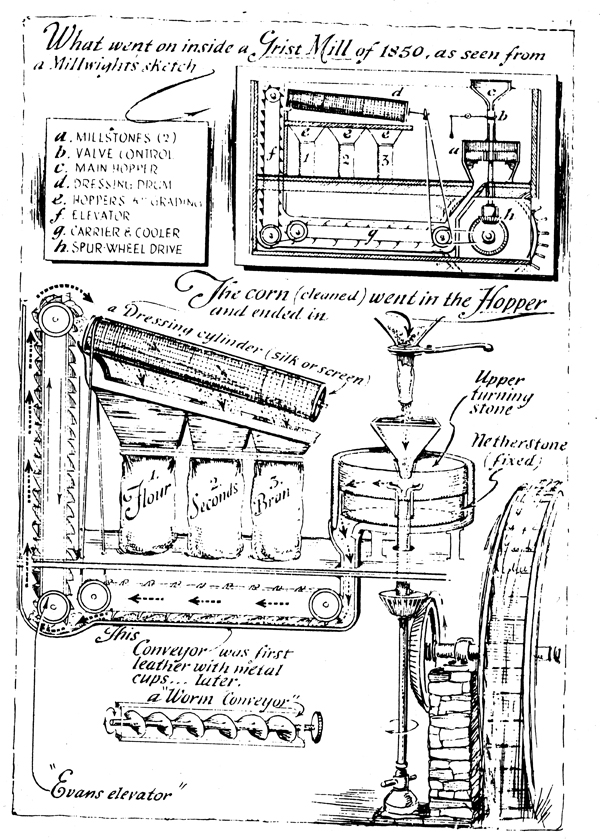

How a Grain Mill Works

In mid-nineteenth century mills, grain was fed to the grindstones through a pipe known as a hopper. The grain was then crushed by the grindstones which moved with the help of wheels powered by the force of the river’s current. The grindstones were marked by furrows that, as they turned one on the other, would crush the grain and push it to the side to make room for more. From here, the grounds were transported on a conveyor belt (also powered by the water wheels) to a sieve-like apparatus that separated the flour from the wheat. (Extract from Hillari Farrington’s article in the Tour de Sutton, Vol. 8, No. 4, Summer 1991).

Towards the end of the 19th century, sawmills were central to Sutton’s industrial development. In its October 16, 1879 edition, The Sutton Pioneer announced that Samual Doray would be building a workshop on Mountain Road (renamed Maple Road) that would be powered by a mill placed upstream on Sutton River. The Godue Casket, a coffin manufacturer, situated on the same road just past the bridge, had its own sawmill. There was also another facing this one, just across the road, where today there still stands an industrial building. Finally, the Sutton Lumber mill stretched the length of the river slightly downstream before the bridge on Principale Street. All these mills were powered by steam created from river water boiled in large kettles.

Water from the mountain, a precious resource

Sutton River is still of vital importance for the town’s population. It provides the drinkable water that makes up the municipal aqueduct system, the history of which goes back to the end of the 19th century…

With a growing city centre, the installation of an aqueduct that was supplied by water flowing from the mountain by gravity became necessary. Between 1885 and 1895, private investors created the Sutton Water Supply Co. and built the first aqueduct with the reservoir situated on the hill to the south-west of Larivée Street.

Sutton became a distinct municipality from the townships in 1896. Barely just elected, the council of the new town planned for the expansion of the aqueduct so as to be able to accommodate the entire population and ensure a more secure protection against fires. The Sutton Water Supply Co. offered to build another reservoir and increase the capacity of its pipers in exchange for exclusive rights to the municipality’s aqueduct system for 24 years.

Before a decision could be made, fire broke out on the night of April 15, 1898 and destroyed some 35 buildings in the heart of the town. As of the council meeting held on May 2, an engineer was charged with the responsibility of drawing up an estimate of how much it would cost to equip the town with an adequate aqueduct system. In the end, although Sutton Water Supply Co. had improved its offer, the town decided to buy the company and alter the system itself.

The rates

The rates for use of the future aqueduct were voted on at the council meeting of October 26, 1898. The bill for a family of six came to $6.00 per year plus $0.50 per additional person. It also cost $2.00 to take a bath or to supply water to a barn that housed an animal. The industrial rates were decided upon later by a ‘Water Committee’.

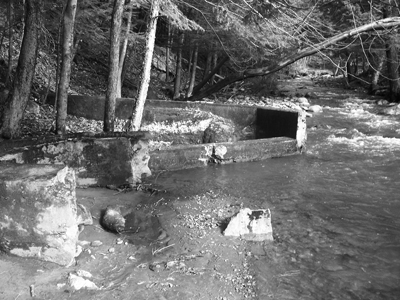

The installation of the new system necessitated two kilometers of pipe and the building of a dam, a water intake, and a reservoir on Sutton River. The exact location for these facilities was chosen by virtue of its solid rocky foundation at the centre of the river on which the dam would rest. Even though today the dam is nearly completely broken down, the foundation is still visible as is the water intake.

The capacity of this new municipal aqueduct system contributed to Sutton’s growth. New industries were established and the Town signed a lucrative contract to supply water to the Canadian Pacific railroad.

At the end of the 1920s, the capacity of the aqueduct was no longer sufficient and improvements needed to be made. A new water intake was put in place higher up in the mountain. As always, it first needed to be ensured that the water would not be contaminated by agricultural activities upstream. As such, in 1936, the Town decided to buy a small body of water, the Mud Pond, and the property situated higher up the mountain from this new water source. They also planned to install the necessary equipment to chlorinate the water.

When Water Turns to Ice

Mud Pond freezes in winter. It was therefore used as a source of ice which was critical for food preservation at the time. The ice was cut in blocks with long, slender specialized saw. The blocks were handled with tongs and gaffs until the point where they would be transported to the icehouse. Farmers would keep their ice in a separate or adjoining building or in the barn and ice merchants used warehouses. In a warehouse, the blocks were stacked one against the other between thick layers of sawdust taken from a sawmill. The icehouse would be emptied as needed until the next winter.